As Remembrance Day approaches, our honour, gratitude and respect for those who fought for all of us erupts in a huge surge of love.

By capturing our ancestor’s war experiences – or someone who is still alive today – we help to breathe life into history texts, and we put a face to those who suffered through conflict: from coast guards, to air force recruits, to military forces. We may be walking through a minefield here as we endeavour to write these stories, but we handle the stories carefully, in order to do our soldier a great honour.

Some of the Mines in the Story-telling/writing Minefield

MINE ONE – we make sure that we know the facts:

We research, research, research, as we get dates, battles, locations, and ranks correct. Our soldier was part of something larger than his own story; he (or she) belonged to a band of brothers, who ate, played, fought, and often perished together. We take responsibility to do our soldier and their band of brothers, the greatest justice possible.

MINE TWO – we mind our views:

War is complex, controversial, and multifaceted. We do not insert our own political views or ethics into the story; unless we are the one who went to war.

MINE THREE – we handle characters carefully:

We always speak and write about others as we would like them to write about us. And we also refrain from grouping nations into a stereotype, unless it was seen that way at the time. We don’t allow our own stereotyping to enter someone else’s war story.

MINE FOUR – we are very cautious of labels like ‘cowards’ and ‘deserters‘:

Unless we know for sure that these were labels used by the person who was in the conflict, then we avoid these types of terms, because they can harm the soldier’s legacy and all those related to him/her.

If we make it through the minefield we have in our hands a well-written, or told story about war; one that shows everyone that we really care.

To indicate what led up to the war/conflict, we –

~ explain the events leading up to the conflict and how well informed those who enlisted may have been.

~ describe the camps, the ranks, the training . . . and then we describe the battleground as we research what this area may have looked, smelled, felt, and sounded like.

~ describe the soldiers’ recreational times: sports, music, entertainment, comrade bantering, and so on.

~ use bold, expressive words when we describe hostile times: grim, cataclysmic, grotesque, mayhem . . . etc.

~ raise up the soldiers and their acts with triumphant words: relentless, glorious, prevail, bugles . . . etc.

To tap into all the senses during this time of hostility, we describe –

~ sights: barbed-wire, flashing lights, blood, flesh, mud

~ sounds: roars, rattles, cracks, screams

~ smells: burned earth, gun oil, napalm.

To look into the many emotions of war, we explore what our combatant may have felt through –

~ fear and safety

~ terror and composure

~ ugliness and beauty

~ honour and shame

~ thrills and depression

~ pity and mercilessness

To wrap up our war stories, we look into –

~ what the welcome home was like

~ any emotional or physical scars left from the war

~ how the military service defined the soldier

~ any recorded material from the war left in our soldier’s name

An episode in combat is a sacred and extraordinary time, only definable by the person going through it, so we handle these types of stories with an unassuming and gentle heart. We handle these stories with great care, so that they may speak volumes about the soldier, and volumes about our handling of this delicate material.

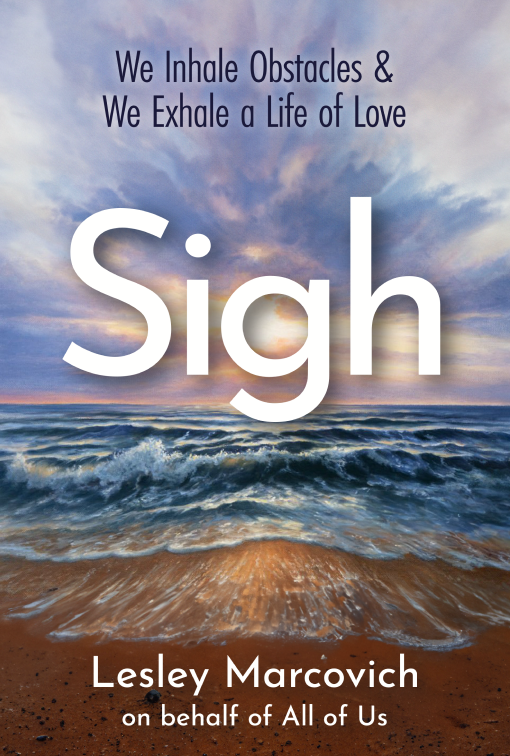

In the book ‘SIGH, We Inhale Obstacles and We Exhale a Life of Love’, written on behalf of All of Us, read more about how we honour and respect one another, and the fourteen layers of who we are, starting with our ancestors – who faced famines, plagues, perilous journeys, and conflicts, with courage and honour – and who still continue to flourish and glorify life inside of us, every single day.